By Asha Bertsch

The newly pig-proofed area is beginning to take on a cultivated appearance! The larapa (Gliricidia sepium) have sprouted, newly planted marigolds are beginning to bloom, the transplanted banana trees seem to be adapting to the change in location, and the passion fruit and damballa (winged bean) vines are taking off (Fig. 1a,b). All are providing a bit of much needed greenery to the fence we built last month. If you’ve been keeping up with the blogs from previous years you may remember that this section of the garden was not blessed with particularly fertile soils. This is the part of the property where a majority of discarded building material ended up and as a result there’s a great deal of sand and rocky fill excavated from the construction of the field station.

However, nearest the fence is an area I really wanted to get cultivated quickly and would need the aid of more fertile substrate. So, as in past years, I’ve had to make a few trips into the forest in search for “kalu pas” or black soil. The task gives me an opportunity to get to know the surrounding soils better. The kekila fern (Dicranopteris linearis) covered slopes behind the field station have some nice dark earth, and are conveniently located, but still a bit gritty with sand and stone. Meanwhile, under the cover of the forest, the earth looks promising. There is a thin layer of dark topsoil, but only a few centimeters deep, before you reach a pebbly subs soil of concreted laterite (baked clays). Even in areas where the soil is a bit deeper, it’s a challenge to find a part of the forest floor that isn’t covered with woody tree roots. Like many tropical forests, much of the nutrients and organic matter here are stored not in the soils, but in the trees. So, I make numerous collections from wherever I can find a good pocket of earth, being careful not to take too much from any one site (Fig. 2a, b). I manage to find some of the best soils near the river or where decomposing trees have collected organic matter. I recently discovered a beautifully dreamy part of the river that is almost completely still, where the light comes down to hit the water like concentrated little beams through tiny gaps in the forest foliage (Fig. 2c). The stillness and dense canopy cover make it a prime location for collecting partially decomposed leaf matter. But my favorite collection spots so far have been in and around fallen decomposing trees. Rotting from the inside out and full of interesting insects and fungi, excavating the organic material from these old logs is a real treat. Some are canoe like in shape, open at the top where fallen leaves collect and decompose the wood that slowly accumulates a rich, dark soil. These are particularly rich pockets of organic matter, sometimes so dark and moist they have an uncanny resemblance to flourless chocolate cake (or maybe I’ve been in the forest too long).

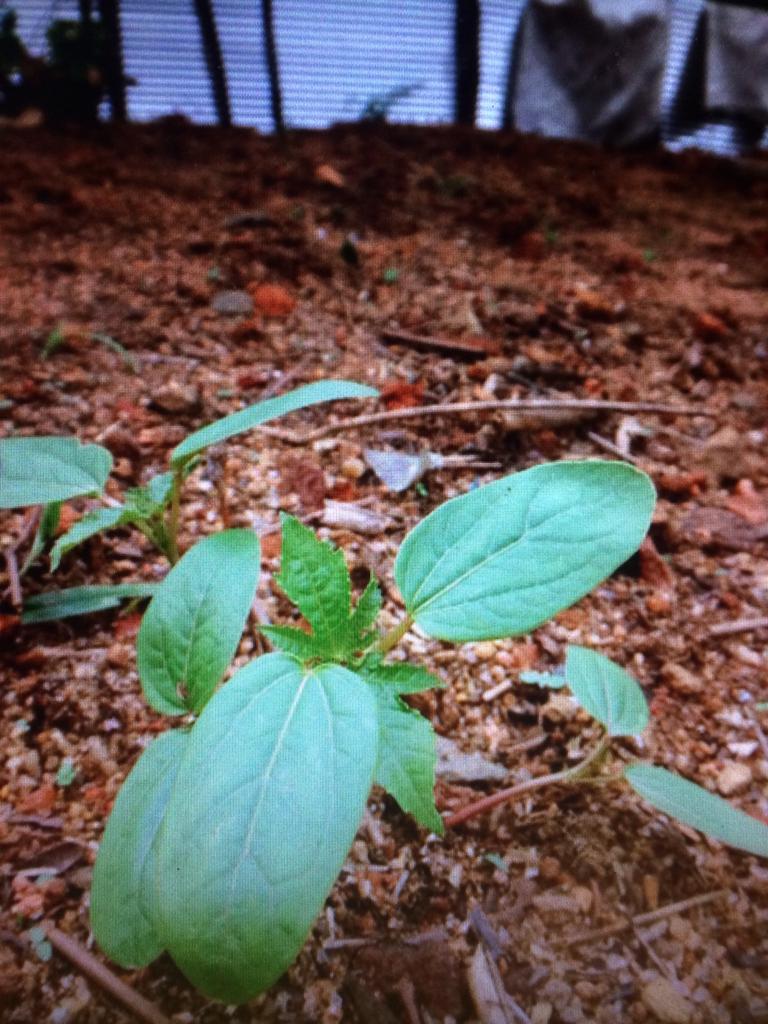

Exploring new areas of the field station and surrounding forest in search of fertile soil has been enjoyable. Hauling the full sacks of earth back to the garden has been less so, and hauling river detritus has been memorable. The anaerobic aroma of half-rotten leaves is one that does not leave your mind (or clothing) easily. But after collecting a buffet of soils from the forest, river, and fern land, I’ve now got a raised bed contouring the length of the fence, where we’ve planted a variety of beans (cowpea, damballa, bonchis (beans), and makarel) and chilis collected from neighbors, as well as a few small fruit trees that were started in the nursery by last year’s fellows (Fig. 3).

Throughout the rest of the fenced area, Piasili and I planted manyoka (Fig. 4), batala, and kiri ale. These species produce edible tubers and are notorious for thriving in poor soils, so we decided it would be the best immediate use of the space. As a side note, they also happen to be the wild boar’s favorite foods. This, along with the recently transplanted bananas, I’m not sure if I’m tempting fate or just looking for some fast assurance that our fencing strategy will work, but it just sort-of turned out that way. So far so good. The true test will come with the rainy season, when the pigs seem to really make themselves known.