By Asha Bertsch

For those who have followed the blogs from past years, you know that Pitakele residents are not subsistence farmers who dedicate great amounts of energy to cultivating fruits and vegetables. Most residents put their time and focus into a single cash crop – tea. You can tell when someone is on their way to their tea garden, or even heading out to tap sap to make sugar from kithul palms (Caryota urens) – they wear attire appropriate for the task. They carry specialized knives and indispensable tools. They have specified times in the day when the work must be done, and a mind for that alone. When folks tend tea, it looks like routine and it looks like work. When they tend the home garden, it looks second nature–like drinking a glass of water while reading! This is an undeniably important task performed without any time having been set aside for it. I find it interesting to imagine how this tangential care of the garden plays out on a larger scale.

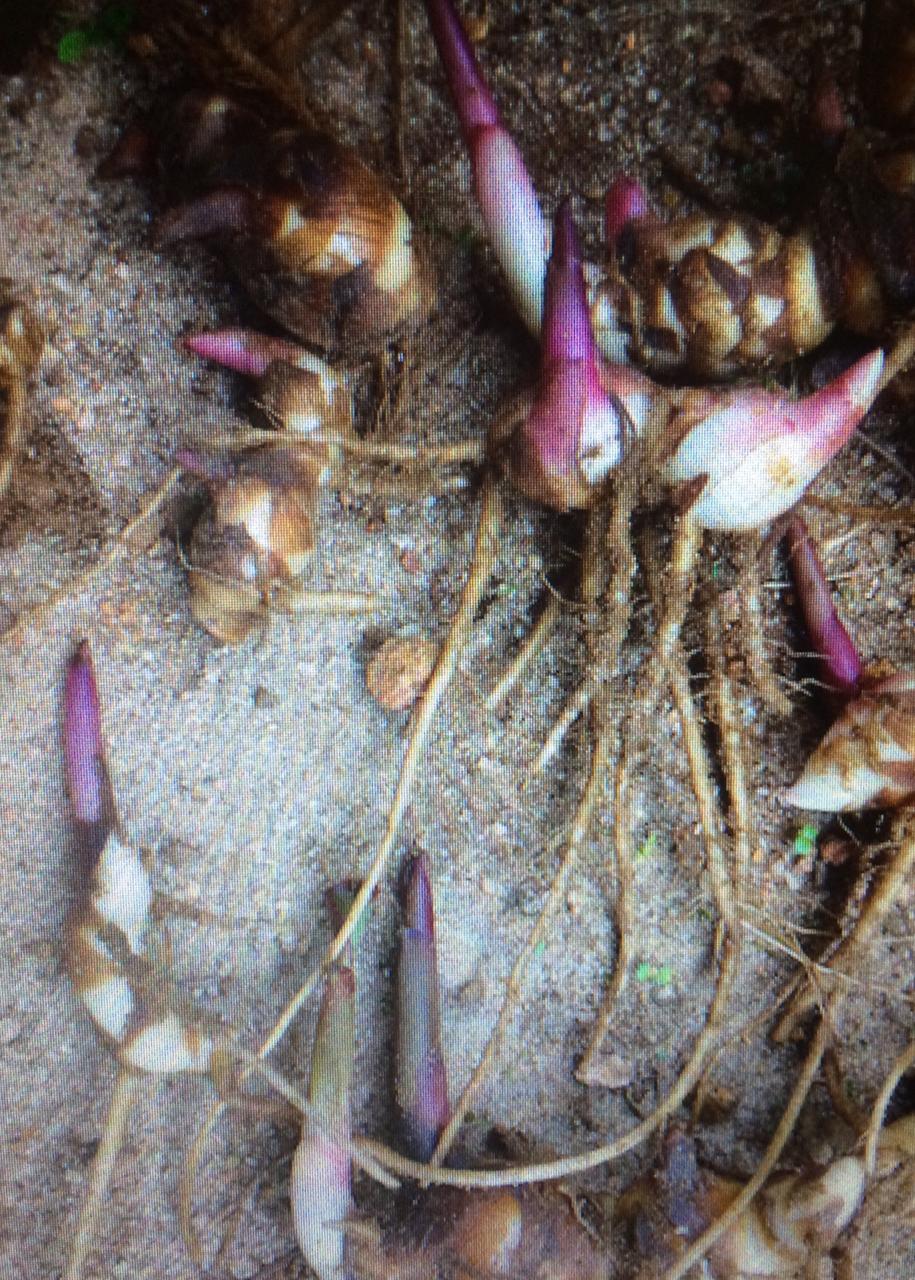

Many of my afternoons are spent visiting neighbors and asking questions about how their plants grow. One question I always ask about is where folks get their seed source. The answer is most often “from other home gardens”. Folks are not investing in the latest cultivars on the market, or looking through seed catalogues. They are simply snapping a branch from a fruit tree they know they like, while casually enjoying a cup of tea at the home of a relative. Whether cultivated by seed “beeja”, “eta” (seed) or “gedhi” (fruit) in Sinhala; or by bulb, branch or root cutting; almost every species in any particular family home garden has come from another home garden, accumulated over years of casual collection. It’s pretty common to see people walking down the village path with a bundle of branch cuttings or folded bits of seed-filled newspaper in their hands as they head home from a visit to a friend’s house. Residents readily brake off a branch or dig up a root cluster to give to a relative, regardless of the original intentions of their visit (Fig. 1). In this sense, the dispersal of over 400 home garden plant species that we have catalogued is somewhat dictated by familial ties and friendships. In a village where everyone is related to someone, so are the plants (Fig. 2). It would be fascinating to do a phylogenetic reconstruction to trace the local origins of different species in the garden. Do they all have a common ancestor from a particularly well-loved garden? Would the seed dispersal patterns mirror the origins of those of families in the village? So many questions!

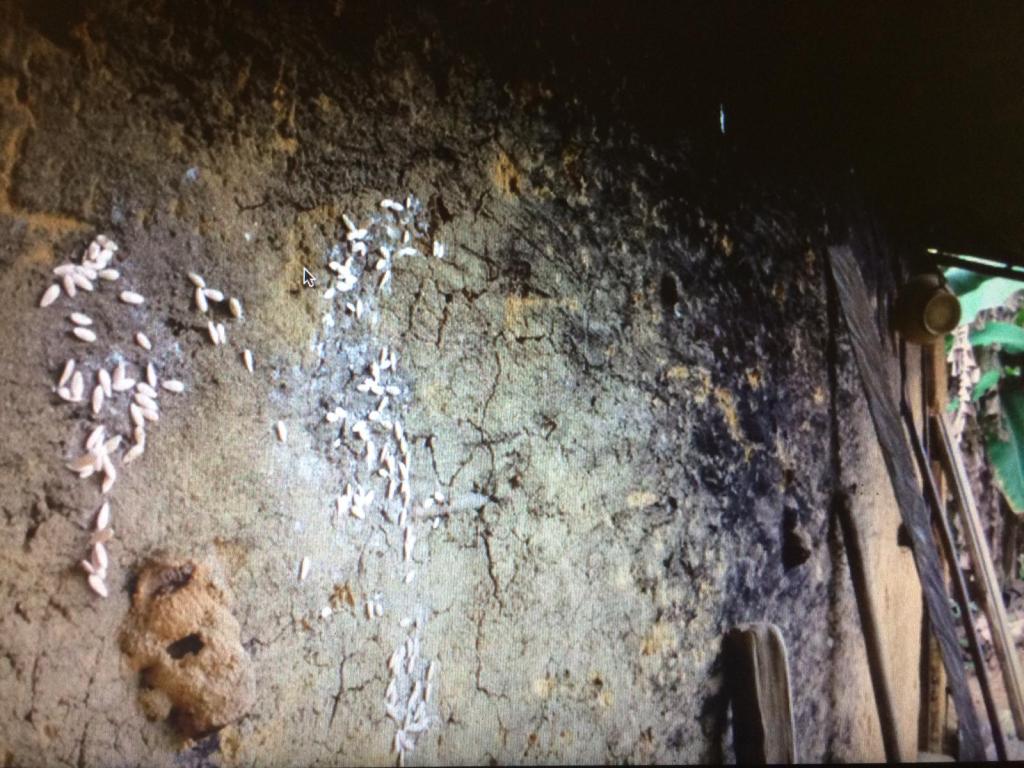

This also has interesting implications in terms of storing seeds–a practice most people in the village seem not to do. Many of the common fruit trees here have large recalcitrant seeds, not well-suited for long-term storage. Most annual vegetables and flowers produce year-round, and most perennial ornamentals are propagated by cuttings (“rikila” in Sinhala), so seeds or branches are always available from a relative or neighbor. Store bought seed packets or small seedlings are occasionally purchased to supplement the stock of annual vegetables like eggplant (wam-butu), and on one occasion I met with a woman who had pasted cucumber seeds to the side of her house to protect them from insects and ground moisture (Fig. 3). But aside from this, most other seed sources seem to be procured directly from the garden at the time of need. Each home garden acts as a live seed bank so other forms to storage are not necessary; and collectively the gardens are the store-house of local diversity. In a part of the world with high humidity and little access to refrigeration, there are many opportunities for decay. Keeping germplasm safe in their own live plants makes a lot more sense.

The second most common answer to the question of seed source, is that seeds are brought by birds! What a cool answer! Another relatively passive but effective planting strategy. Birds visit one garden to eat the fruit and deposit seed in another. Once sprouted, residents can decide whether to keep the new sapling where it’s landed, transplant it, or get rid of it altogether. Interestingly, in terms of genetics, this is roughly the same as the first answer, in which plants move from garden to garden. The added complexity being that birds will visit fruit trees deeper in the forest more often than people do, and so may occasionally add new genetic material into the mix. Birds are attracted to the gardens not only by the fruit of trees, but also by offerings made by people. In almost every garden is a bird feeder of sorts– a wooden post with a plate of woven bamboo or flat piece of wood anchored on top, upon which leftover rice and fruit scraps are offered to the birds and squirrels (Fig. 4). If someone is eating a banana or orange they’ll often toss a chunk of it up onto the bird plate. I find this really interesting because this is also a strategy used in tropical forest restoration– erecting bird or bat feeders on degraded land to recruit seed sources brought by birds or other flying animals. I haven’t yet figured out if there’s a deliberate connection here, but feeding the birds is definitely an important ritual for many folks in Pitakele. One woman in the village left town to visit her mother and upon returning, had much to say about her husband having let the birds go hungry in her absence.

So, people plant the gardens, birds help plant the gardens, people and the gardens feed the birds, and birds and people perpetuate and cross pollinate the gardens from within and across the villages (Fig. 5). It’s fascinating to think that whether by bird or human (or giant squirrel), several hundred species of fruit tree, spice, timber, Ayurvedic medicine, and religiously significant flower are being dispersed in ongoing circulation from one home garden to the next.